Alexis Bonogofsky honors the prairie

Welcome to Big Sky Chat House— a newsletter exploring the state of Montana with the artists, activists, politicians, and movers and shakers that call it home. You can earn yourself some Instant Karma by subscribing below!

** Friendly reminder: If you found this email in your Promotions folder, please move it to your Primary inbox. That will make it easier to find down the road, and teach Gmail to send it to other subscribers’ Primary inboxes as well. Thanks! **

Wow. We’re already at our last interview for 2022! Thanks so much for your support and feedback on the journey so far.

In this week’s newsletter, we’re going to turn our attention to the glorious grasslands of Eastern Montana to hear from Alexis Bonogofsky, a photographer, community organizer and rancher.

Among other roles, Alexis currently manages the Sustainable Ranching Initiative for the World Wildlife Fund, where she and her team collaborate with ranchers across the Northern Great Plains—which includes portions of North Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, South Dakota and Nebraska, as well as Canada—to ensure the viability of the region’s grasslands and wildlife.

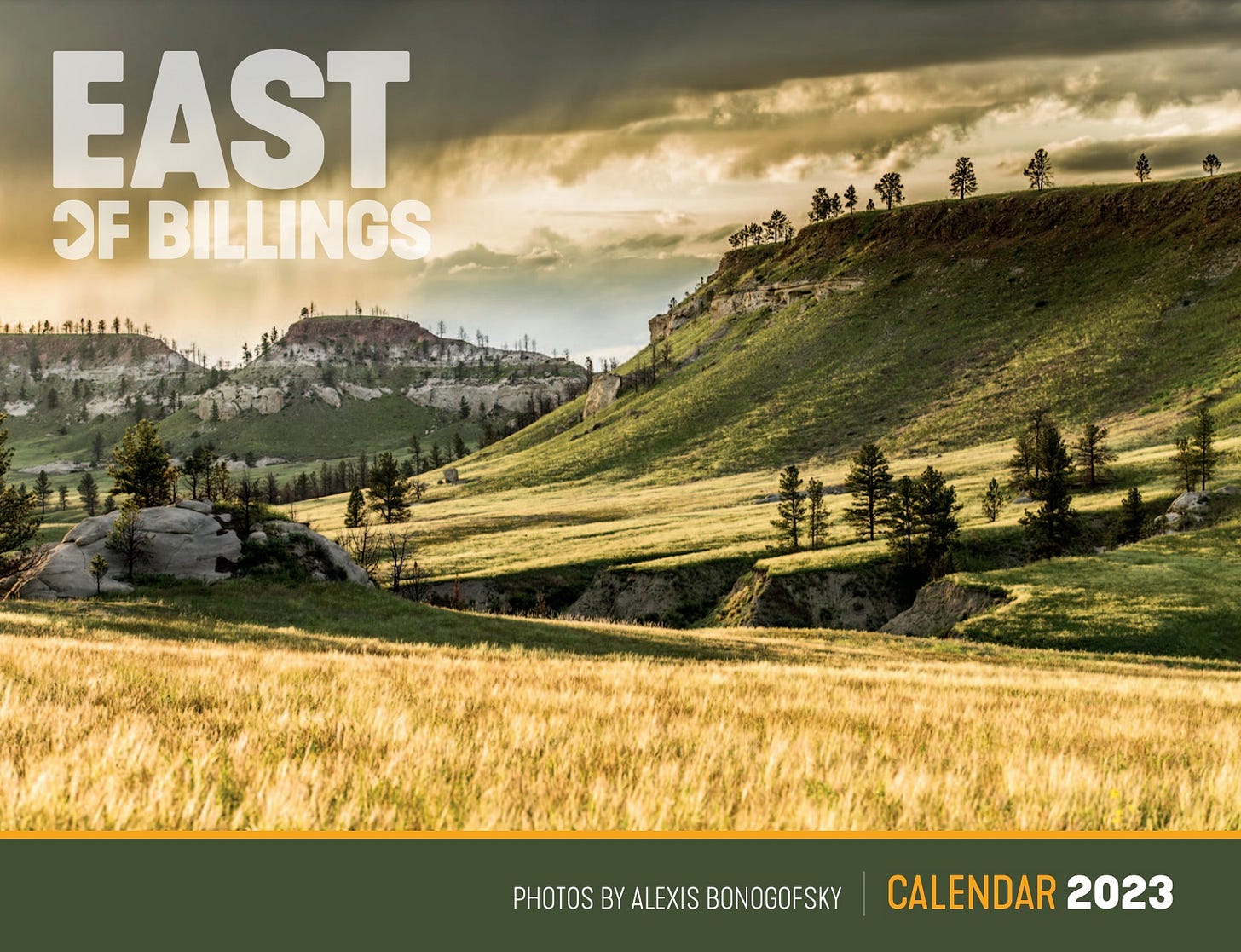

Alexis additionally recently relaunched her “East of Billings” calendar series, which features her stunning photographs of Eastern Montana and the people and wildlife that call it home.

You can check out the calendar, which is available for purchase, right here.

(Disclaimer: Alexis additionally serves on the board of Montana Free Press, where I occasionally contribute as a freelance writer.)

Our conversation focuses largely on the ways her career intersects with this moment in the state’s history: how she uses photography to document lands whose ownership is often in changing hands, and champions sustainable ranching as a means of resilience in the face of a changing climate. We also discuss her intention to engage with the imminent 2023 legislative session on environmental bills, and the 2011 oil spill that helped fueled her activism.

Max: What does the phrase ‘East of Billings’ mean to you?

Alexis Bonogofsky: It originally came from my friend, a cowboy poet and a rancher in Eastern Montana named Wally McRae; many Montanans will recognize that name. When he and myself and a lot of other people were working on stopping the Tongue River Railroad and the Otter Creek coal mine from getting developed, he would always say that no one cares what happens “E.O.B.”

All of this stuff can go on in Eastern Montana and a lot of people in Helena and Western Montana just don't pay attention. Maybe it’s thought of as a sacrifice area for some things. And so I started East of Billings [which is also a blog] as a way to bring people's attention to the fact that a large part of the state is in Eastern Montana (laughs) and what happens here matters.

It's beautiful and it's worth paying attention to. It’s this wide swath of of prairie that so many people love and sometimes it just gets ignored.

How did you get into photography?

I never intended to be a photographer. It wasn't in my career goals, but when I first started working a lot in Eastern Montana, I was disappointed with the images that I saw in newspapers and different places. It just didn't hit me that the photographers out there were actually seeing the beauty of Eastern Montana. They certainly weren't seeing what I was seeing. And so I bought a camera, a nice camera, and I taught myself how to use it. I just wanted people to see the landscape how I saw it. And then it turned into something I didn't quite expect initially.

I'm a prairie person. I love the prairie and it's where I feel most at home. And so when I am in the grasslands I can see I see the beauty there and I know when the light is gonna be right. Or I see the little things, the little critters like the toad on my calendar that you wouldn't even know lives there unless you’re paying attention.

Are there other photographers that have informed your approach?

I first thought that [photography] could be an option for me because of my friend Ted Wood, who is a photographer and a western guy. He’s shot for Vanity Fair and was one of the first guys that got photos of the big fire in Yellowstone back in the eighties.

I was out with him at the Fort Peck Reservation when I worked for National Wildlife Federation. He was taking photos for National Wildlife Federation of the bison. And I watched him and I noticed when his eyes lit up, when the light hit in a certain way and how he saw the landscape and how you start to see it differently when you have a camera with you.

And so I just got to follow him around for three or four days and watch him work. He really inspired me.

Coming to photography later in life, and teaching myself, I didn't have any rules in my head. I didn't mean to do it as a career or for money. So there wasn't anything telling me I had to do it a certain way. I just started taking pictures. Some people say they know when [they see] a photo of mine, and I don't know what they mean by that. I have no idea what my style is (laughs).

Well then I guess I can check that question off my list. Do you often have a camera with you when you're out and about in the world?

I always have a camera or numerous cameras in the car with me when I'm out. And one of the problems I have is that I constantly want to stop and pull over to take pictures.

You never know when something amazing is going to happen. And usually with the light in Eastern Montana, you're always gonna hit something pretty cool at sunrise or sunset.

I always say that mountains get in the way of a good view. When I'm in the mountains I always feel a little closed in. In the prairie, I can see in every direction for many miles.

I love the cover photo on your 2023 calendar; it’s so striking.

That's probably one of my favorite photos I've ever taken. It's from a ranch north of the Northern Cheyenne Reservation.

It’s a photo I took about two years after I got my first camera. It's right near Deer Medicine Rock where Crazy Horse carved his vision of his death into the stone. There's a lot of historical and cultural importance in that valley.

For me, this photo shows that Eastern Montana isn't just flat (laughs). A lot of people don't expect Eastern Montana to have varied topography: these hills and sandstone rock formations and petroglyphs. This ranch was one of those ranches where I would go and just practice with my camera.

I’ve met environmental reporters who describe their work as akin to that of a coroner or mortician: they’re documenting something that is disappearing. Does that idea resonate with you?

Yeah. I don't think “grief” is too strong of a word to use, for a lot of reasons. It's climate change, it's how Montana's changing [with] more people moving into the state. The places that I used to go when I was a kid, we'd be like the only people there. And now there's hundreds of people on the trails. It’s knowing that it's never going to be like it was. There are absentee landowners coming in and buying up family farms and ranches and turning them into their private hunting grounds; all these things that I think most of us see and it almost feels like you can't do anything to stop it. I think there's grief associated with that.

Even that ranch where I took that picture, the rancher, my friend Nick, he passed away this year. And his kids aren't ranchers and so they're selling the ranch. I imagine it will be bought by someone from out of state and [used] as a hunting property because it's hard for anyone in agriculture to afford the land prices anymore. I'll probably never get to go back there ever again. It's awful to think about. In a sense, you're documenting things that you feel will never be the same.

Perhaps on a slightly cheerier note, I’d love to talk about the WWF’s Sustainable Ranching Initiative, of which you’re the manager. For starters, why do the grasslands need to be preserved?

We've been seeing the conversion of grassland into cropland happening at a fairly alarming rate in the Great Plains.

Intact, large-scale grasslands provide habitat for lots of wildlife. A lot of grassland birds need grass—and not cropland—to survive. The Northern Great Plains is one of the largest intact temperate grasslands on the planet.

It's also important for climate change reasons. Our grasslands store a lot of carbon, and if you plow up grasslands, you're releasing [that] carbon into the atmosphere. It's also important for ranchers to have grass for cattle to eat. If we have our grasslands converted into croplands, then that [means] less space for cattle ranching.

To participate in the program, a rancher “enrolls” their land; what does that entail?

They basically agree to certain things and we provide certain resources. They agree to no conversion of their grasslands for ten years. And they agree to develop a grazing plan, if they don't have one already, that helps them work towards regenerative grazing, which is a rest-rotation plan where they move the cows more often and give the grass time to rest.

They also agree to let us do ecological monitoring on their ranch: taking baseline soil health indicators and water infiltration and bird surveys. And then agree to participate in educational trainings on grazing wildlife monitoring and financial skills related to ranching.

In return they get money for educational scholarships, basically grazing schools or ranching-for-profit or different trainings. And then the monitoring that we conduct is free to them. And then we also help pay for ranch infrastructure projects: water projects or electric fences or different things that allow them to move their cattle more frequently and rest their pastures. And then they get access to technical assistance. So if they need someone to help them with a grazing plan or an engineer to help them with their water project, anything like that, we can help pay for that technical assistance.

The WWF website says the program hopes to enroll one million acres by 2025. How close are you to that goal?

If I remember correctly, we're working with 63 ranches and we're at about 600,000 acres.

Our goal initially was a million acres in five years. I think we'll probably hit a million acres within the next year.

Ranchers all over the Great Plains are super interested in this program. And we haven't even had to do much advertising; it's mostly word of mouth.

In the upcoming 2023 legislative session, lawmakers may pass laws, or craft constitutional amendments that will in turn be put to voters, that directly impact the environment. Do you anticipate engaging with the political process in the context of the Legislature?

I think part of the reason that I care so much about environmental stuff that’s relevant to what's happening in the Legislature is that when the Exxon oil spill happened in 2011, it flooded my farm with oil. And so that’s when I realized that when you're directly impacted by something like that, it's different [than just] reading about it.

And so for me, the legislative work, and making sure that our constitution stays how it is, is important on that personal level.

What's a lasting memory or feeling from that experience for you?

One of the biggest things to me was that you felt like you were on your own in a lot of ways.

I felt like there was no one advocating for the public. The company and the EPA and the state, they're all kind of working together, and the public's out there not really knowing what's going on or knowing how oil impacts your health or the environment.

The thing I learned was that you can't really clean up a river oil spill. Once the oil is in the river ecosystem in the river, it's just kind of there, and it gets dispersed. And the whole quote unquote cleanup was just a public relations show from Exxon. You see guys in white suits and you're like, Oh, they're cleaning this oil up and it's gonna be gone. And that's not true. I think they spent like $135 million on it. It makes you slightly cynical and you realize that when you're a member of the public, you have to really advocate for yourself because there's not really anyone doing it for you, you know?

[In regards to the 2023 Legislature], we'll see what sorts of bills pop up and what rises to the top. I could see myself going to Helena to organize comments and talk to people about it. My background is in community organizing and that's [still] extremely important to me. My goal in 2023 is to reactivate my East of Billings blog and write more about this stuff.

It’s not part of my job, to do legislative work. But as an individual, I will one hundred percent be engaging with the Legislature and doing what I can.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Well, that’s all for today, folks. Thanks for reading, and we’ll see you in 2023!

In the meantime, you can always reach me via email, the comment section below, or on the Elon Machine, @SavageLevenson.