Sen. Daniel Zolnikov hypes his wide-reaching data privacy bills

Plus: The Pulp takes off, and I write an album review!

Welcome to Big Sky Chat House— a newsletter of candid conversations with movers and shakers in Montana.

If you found this email in your Promotions folder, please move it to your Primary inbox. That will make it easier to find down the road, and teach Gmail to send it to other subscribers’ Primary inboxes as well.

Since he was first elected to the state legislature a decade ago, in his mid-20s, Republican state Senator Daniel Zolnikov has made data privacy a central tenet of his political philosophy and platform.

Yet, he says—despite several other significant privacy policies enacted in Montana, from limits on facial recognition technology and location data—it’s taken a long time for momentum to build on consumer data privacy, specifically.

2023 proved to be a watershed year for Zolnikov’s bills. The legislature passed his Genetic Information Privacy Act and Consumer Data Privacy Act, and Governor Gianforte signed both into law this spring. The genetic privacy bill goes into effect this Sunday, October 1. The consumer data privacy bill will take effect exactly a year later, on October 1, 2024.

Both bills cover large swaths of data. The genetic data bill is particularly cutting-edge, and comes as genetic data-collecting technology becomes more advanced. The consumer data bill prevents a business from tracking, sharing or profiting from the data we all generate as we interact with the internet.

Earlier this month, I caught up with Zolnikov to hear more about the bills themselves, the value of data privacy, the unsavory lobbyists that fought his bills and what he thinks about Montana’s Constitutional right to abortion being posited as privacy.

Max: Why have you focused so much of your time and energy on privacy issues?

State Sen. Daniel Zolnikov: It's now been over ten years, so that is a lot of time and energy (laughs). I ran for office at a relatively young age; I was 24 or 25 when I filed. I had a buddy—we both had information systems degree from the same college, graduated the same year—and he said, “There's not a lot protecting people's privacy and that seems up your alley.” That little conversation has dictated a lot of time in my life over the years, and that friend [Eric Fulton] has been very supportive and insightful as well.

But it went from [my] first session trying to do a privacy bill and having like 38 lobbyists come in and destroy it, to this last session, which was just awesome. If someone told me even two to four years ago that this bill would get passed, I would have said no way.

What do you think has changed in the past few years?

One of the main things is that a few states have passed different versions of that type of legislation. The ball was rolling. It's a proven concept. It's not like if we pass this, you’re gonna kill all these industries and the sky's gonna fall. [A similar bill passed] in Connecticut, and Connecticut is the headquarters for some telecoms and they're doing just fine. It really takes the wind out of the sails of the oppositional argument.

There’s a Politico story about your work that includes some unflattering portrayals of the lobbyists who fought these bills. Can you describe your relationship with those lobbyists, and whether their actions surprised you?

There's two sets of two types of lobbyists, just to simplify: You got the local guys on the ground in Montana, from Montana. They can range from insurance to ag, whatever. But they know the legislators, they know the process here. [I didn’t deal with] our local guys [on these bills].

Then you have the national people who are trying to cover tons of states, or they're working for a entity that is trying to track this stuff all over the country. So they don't know the people. They don't know the flavor of our legislature. They're just the big contracts.

And then there's of course DC [policymakers], but we don't talk about DC, because that doesn't affect this.

Sorry, are you making a joke about DC? I couldn’t tell.

No, no. They don't care about us. [Lawmakers] in DC, they spend trillions of dollars. We have a, what, $10 billion budget.

They are not influential in this story except the fact that they're really good at not getting anything passed, which is why we pushed this privacy law in particular, because they won't actually do something at the federal level. Then we say, fine, we'll just start passing these types of bills across the nation and you have a patchwork to deal with.

Do your job or I'll do your job for you, is how I'd look at it. So that's the only time those guys need to enter the conversation from my perspective.

Am I painting with too broad a brush to say that the lobbyists were uniformly attempting to handicap your work on privacy?

It looked like they were bringing something to the table, but really the goal was to chip away at the old block and/or water down the legislation.

[The Consumer Data Privacy Act] is a 20 page bill. I ran over twenty bills this session, and fifteen became law. I don't have personal staff; I have to know the bills. I don't have my person who can write me my talking points; negotiating the bills, like that's all on me. So that includes learning the language. A 20 page bill is not easy.

I thought it was starting out as a pretty healthy conversation [with the lobbyists, who would say]: “These things are problematic from a regulatory or from a functional aspect, and this is an issue here, and can we change this wording here? It doesn't really do much.”

I'm like, oh yeah, that's fine. But then it ended up not being fine because those changes were actual major changes, not minor functional changes.

What's an example of something that at first glance maybe seemed like an innocuous change, but proved to be more substantial?

One is the “right to correct.” [In the lobbyists’ proposed bill], if I had requested my data be deleted or ported, and I catch that they're sharing it—which is very hard to do—they would have had six months to correct it, but they'd never be held accountable. There would never be any actual state action against the company breaking the law. My bill basically would've had a huge loophole that said the bill doesn't really matter if you get caught, you get six months to fix it.

We don't want to be a sue-happy state, but if they always just get to fix it when they're caught, they would never be held accountable.

Now that the bills have passed, have you heard from any of those lobbyists? Do you have a sense of whether they're planning any sort of recourse?

I heard from one of the large companies—I'll leave their name out of it. I ended up dealing with them at the very end in a very positive way. [They] said there will be some changes with how they do things because you can't say different things to different legislators in different states on the record.

[They told] a lawmaker in Maryland, if you do the Connecticut bill, we'll be more than happy to support it. But I started with the Connecticut bill and they said, “Can you make all these changes to it?” Why does Maryland get the Connecticut bill and Montana get a lesser version of the Connecticut bill?

Another thing I heard was that some of these companies don't really care about Montana and they're not going to enact some of the provisions in the law because they think the Attorney General will be too busy to actually file any suit. Now that I know that, I'll be the first one, when the bill becomes law, to do all the requests and make sure that everything is being followed to a T. I'll be the one requesting the suit.

For the genetic privacy bill, your data now has whole new guidelines—your DNA, basically—has new guidelines in Montana. So the companies have to follow it. If you find that a company did not follow the laws—say you request something be deleted like the destruction of your biological sample, or you request a deletion of your consumer genetic data or things along those lines—and it doesn't happen, then the Attorney General can initiate a civil enforcement action against the entity.

At the most elementary level, what is the value of data privacy?

There’s a lot of data points about a consumer, but people don't know how it works, how it's collected, how it's shared, how to opt out and that they have no rights regarding it.

The flood gates have been opened, but we have a possibility to actually start to close them down and give consumers their rights regarding their own data and information.

If I'm paying for services, why do those entities also get to double dip on a business model where my data [presents] another way to make money?

Is there anything else you want to highlight about the genetic privacy bill?

There's no law like this in the nation that protects people's genetic law or genetic data like the Montana bill. This is actually probably the law I'm most proud of because I think this is the issue of the next hundred years. Genetic data can tell so much about you that you don't know—not just health issues or when your hair might start falling out or turning gray—but there are other sides to it where [an entity] can correlate whether criminal activities are likely to come with a similar set of genetic code. There is a whole different world out there.

As we get more sophisticated, you'll be able to identify trends of what someone will likely do. You can now profile someone for not just marketing, but for all types of things. So add that to the fact that we can now easily collect DNA—they can just basically pick up a ton of DNA all at once, [like] on beaches.

You could basically profile everybody—that's all possible right now—and you don't have any rights over that except now in Montana. I think that bill is the future.

I recently started reading Tyranny, Inc., by the conservative writer Sohrab Ahmari. The book argues that tyranny can come from the state itself, but also from private corporations. Do you see corporations’ attempts to use our data as tyrannical or nefarious?

The simple answer would be yes. A lot of it's profit motivated. But the flip side is that, like with the NSA scandal ten years ago, most of that information is collected through the back doors of private companies.

Power that is granted is usually utilized. It could be two years down the road, ten years down the road, or 50 years down the road. But when we sent the NSA to track terrorists, it [became] okay for the NSA to track all Americans and make sure they're not terrorists.

[Public and private entities] typically work hand in hand. So if you only stop one side, you're not stopping the other side. You need to really put some reforms on both to make sure people’s rights aren't being trampled.

Before we wrap up, I wanted to ask you about abortion access in Montana. The standing interpretation of the Montana state constitution is that the right to an abortion is protected on the grounds of privacy. Considering your background and expertise in privacy, I’m curious what you make of that.

That gets muddy pretty quickly. So that's the Armstrong decision, utilizing the right to privacy on abortion. It's no big secret that the person who wrote that decision [former state Supreme Court justice James Nelson] is extremely partisan—you can read his is op-eds in the paper every month.

So there's questions of whether that decision was rightfully made. What I've worked very hard to do is try to make digital privacy something that isn't partisan. Everybody works together on the digital privacy stuff; bringing in abortion would just kill the consensus and ability to work together.

I wouldn't say it's a cop out, but I would say it's just keeping the focus on what you can accomplish. Because [regarding abortion], everybody's got their mind made up, it seems, and you're not gonna change anybody's mind. All you're gonna do is create enemies utilizing the topic where we could pass a lot of cool laws.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

One more thing (or two)…

Over at Montana Free Press, I spoke to Erika Fredrickson and Matt Frank, the co-founders of a brand-new (and free) digital publication focused on all things Missoula called The Pulp, for “The Sit-Down” column. You can read the interview here.

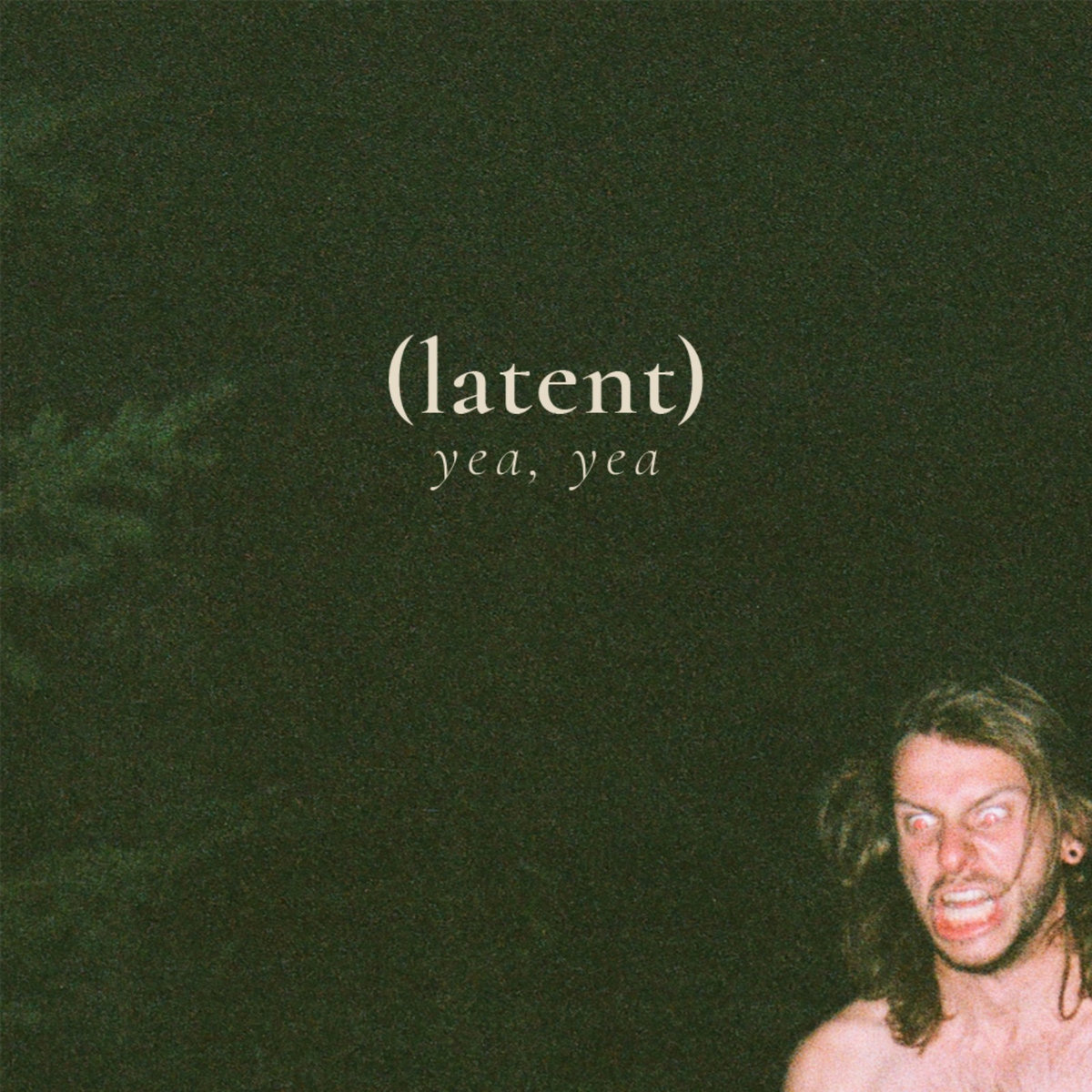

And then, whaddaya know, I made my debut at The Pulp with this review of Missoula’s terrific, Nirvana-influenced punk trio (latent). Bon appetit.

Thanks so much for being here. In the meantime, you can always reach me via email, the comment section below, or on the Elon Machine, @SavageLevenson.