Stella Nall's whimsy and heartache

Welcome to Big Sky Chat House— a newsletter exploring the state of Montana with the artists, activists, politicians, and movers and shakers that call it home. You can earn yourself some Instant Karma by subscribing below!

** Friendly reminder: If you found this email in your Promotions folder, please move it to your Primary inbox. That will make it easier to find down the road, and teach Gmail to send it to other subscribers’ Primary inboxes as well. Thanks! **

To explore the work of Stella Nall is to enter a fantastical world of creatures—some easily identifiable, some rendered magical and weird by stretched-out limbs, the addition of extra heads and human hands and floating crowns—generally painted in bright acrylics, with beads occasionally adorning the image.

While Nall embraces the playful nature of her own creations, her art also serves as a vessel for her complex and fraught relationship with her own heritage and identity.

Nall is considered a First Descendant of the Apsáalooke (Crow) tribe, but has been denied enrollment as a tribal member, despite her familial and cultural connections. The tribe employs a measurement known as blood quantum to determine an individual’s “Crow blood,” and thus, their eligibility for enrollment. Per the tribe’s specific requirements, Nall does not qualify. (Other tribes employ various methods for calculating blood quantum and eligibility, writ large.)

While First Descendant status grants Nall certain benefits, her inability to gain enrollment has had a large impact on her life and career.

She addresses this complex dynamic in some of her “Creature Creations,” as well as her growing body of abstract paintings, commissioned murals and poetry.

In a few weeks, Nall will release a prototype of a book of poetry and illustrations via the NYC-based Women’s Studio Workshop, called “Steel Wool on My Stomach.”

Nall and I caught up for coffee on a snowy evening in Missoula to dig into the nuances of her relationship with her cultural heritage and how it manifests in her art.

Stella Nall will give a free and online presentation about public art today at noon via Open AIR Montana. You can register for the event here.

Editor’s note: This interview originally noted that the Eiteljorg Museum only accepts works of art made by enrolled tribal members. That is not the case.

Max: For folks who are unfamiliar, can you help explain how the blood quantum determines tribal enrollment?

Stella Nall: When the US first made contact with the tribes, the census was trying to record people's citizenship and determine whether they were an enrolled member. They basically made a list of everyone who was around at the time and arbitrarily determined what percentage of Crow they thought that they were. There aren’t really any notes of the standards they used, but I'm presuming it was stereotypes about what people looked like.

The Crow land bordered a lot of other tribes’, so there was quite a bit of intermixing, but that wasn't really taken into consideration.

The standard was set at one quarter blood. If it's [the child of] two Crow people, then the blood quantum gets added together. But if it's a Crow person and a person from another tribe, then it gets cut in half. The idea was to quickly dissolve Crow citizenship so that the government wouldn't have treaty responsibilities to uphold.

During that time the Dawes Act was also [in effect]. Basically people had to claim either a certain amount of Indian blood or they had to give up their rights to their land, depending on how Native they claimed to be.

If they wrote down half or less, then they got to keep their land. If they claimed higher, then they had to have an appointed person help watch over everything, which I think led a lot of people to write down less than [was accurate].

That’s what we think happened in my family because everyone that we know, up to my great-grandparents, lived in Crow Agency and was fluent in the Crow language.

[My great-grandmother] wrote down that she was half Crow; there weren't any records on what the other half was.

My grandpa lived in Lodge Grass, but he didn't register with the tribe at all, so he wasn't enrolled. And since my [grandmother] was also registered as half Crow, then my mom’s a quarter, which is the limit for the blood quantum. My dad's non-Native, so my brother and I are registered as one-eighth; that's considered a First Descendant, but not an enrolled member.

[As a First Descendant], we're not allowed to vote on any tribal matters. It's really frustrating to me because tribal enrollment is considered this standard that's supposedly equitable across tribes, even though the methods of determining it are unique to [each] tribal nation. Some tribes have lineal descent, so if your parents are enrolled, then you get to be enrolled. Or if they have blood quantum, they might consider other tribal lineages; your total degree of Indian blood. But Crow only considers Crow blood.

[Enrollment] determines a lot of different things outside of tribal citizenship. I've been really interested in placing work in Native-led institutions. But [some] places that I really look up to require enrollment for you to participate or present work to be acquired to their permanent collections.

Have tribal officials been open to having this conversation with you?

So far very not much, which is super disappointing. The first time we reached out was when I was a kid. My mom submitted an enrollment application for me even though she knew the current blood quantum would make me denied, but she was like, we have all of our lineage for our family tree and this is my cultural connection to the community and these are my kids, can you please enroll them? So I have all those documents from when I was a baby.

And then when I started working on this [project] in 2019 or 2020 I was really curious because I thought for most of my life that everyone endorsed the blood quantum. But I started listening to podcasts by other Indigenous people and reading about how different tribes determine enrollment and I realized that most people are moving away from it now. So that made me really curious as to why we were still imposing it.

I had emailed the enrollment office and asked them if there is a way that we could have the members vote on the current enrollment policy. They didn't reply and then I emailed them again and cc'd a bunch of the tribal officials.

One of them eventually [suggested that I] write to the legislative office. I've written them a few emails I never heard back. At that point I was still not sure if [other people were in the same situation]. In my experience, people don't really talk about their blood quantum.

But then I put a little poll on the tribal Facebook page and was like, Hey, I'm working on my BFA for the University of Montana and I'm wondering what percentage of people support the blood quantum.

I forget the exact percentage, but a large majority wanted to switch to lineal descent. There were some comments concerned that if we switch to lineal descent then there'd be a huge influx of people trying to enroll that don't have any connection to the culture.

[There are] ways to mitigate the issue. And the big one that I think we could use if we did switch over would be to use cultural competency interviews. There's still room for a lot of problems with that. But I think at this point, it’s the best option. But I'm still doing lots of research and trying to see if there's anything else.

How do these emotions and experiences manifest in your work?

I'm really grateful that I have artwork to try to process through some of these things. It's very difficult because I culturally identify as Crow, and all of my mom's family speaks Crow.

My grandma—my mom's mom—was sent to assimilative boarding school [but] her siblings weren't sent. So all my cousins speak Crow and my mom never learned. It adds this other layer of directly seeing the impact that a lot of US policies can have on Indigenous families.

There's a lot of feelings of inadequacy, or not being able to speak my language and being disenrolled.

I grew up in Bozeman, which is a predominantly white place. I was tokenized a lot as a kid. A lot of my childhood I was embarrassed of being Indigenous [and tried] to push it away.

When I moved to Missoula I ended up making a lot more community of other Indigenous people and I [reconsidered] the parts of my culture that I had been putting distance [between], like going to powwows.

My mom is a really good bead worker and she tried to teach me when I was a kid, but I wouldn't learn because I was embarrassed. But I reconnected with her over FaceTime when I was in college and she taught me how to bead. I'm still learning a lot.

I have some “Creature Creation” questions for you. What inspires the creatures?

I've drawn similar things since I was a kid. I've always just thought that they would be silly little friends to imagine walking around. Sometimes I’d just think about something that would make me laugh, like a big cow with little hands, and there's not too much significance in it beyond that.

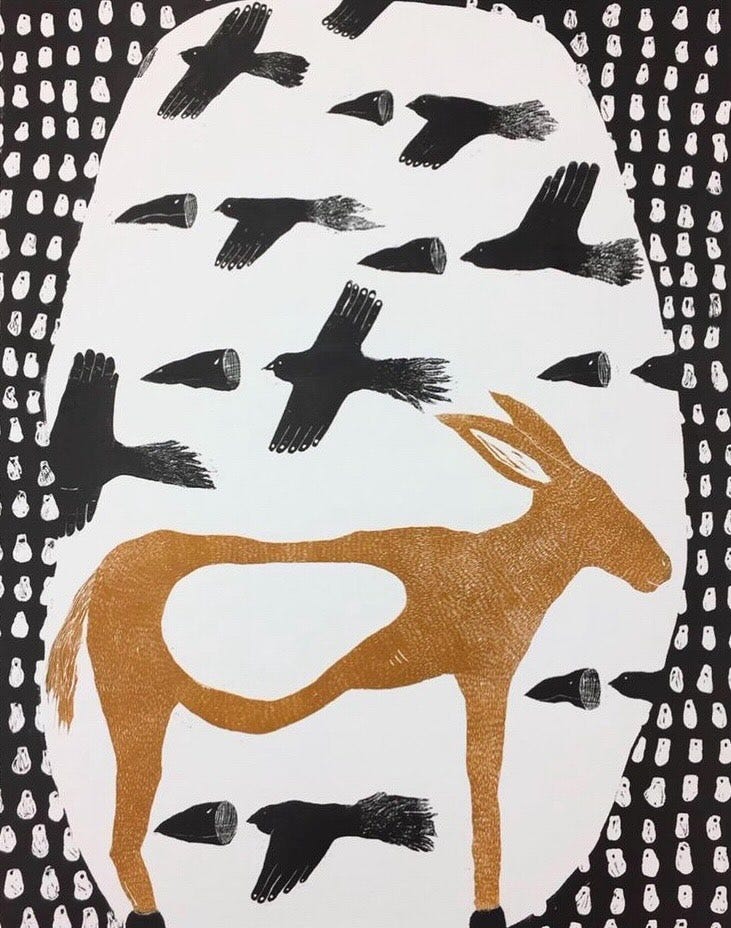

But then some of it is the more important work that I do. Like the piece that started the body of work that I'm working on about tribal policy and such is called “First Descendant: Sterile Hybridity.” It's this big woodblock print.

It was the first time that I used creatures in a more serious way. It’s kind of funny to call them serious because they’re hand birds.

Some of the imagery is drawn from tradition. The background is elk's teeth, which are a really important component of women's regalia for Crow. When I was a kid my first outfit for powwows was an elk's tooth dress. I’ve internalized that as a symbol for my family and connection to my tribe.

The birds speak to the feelings I was talking about earlier, of inadequacy and not being able to meet the standard for enrollment for my tribe. The Crow word for ourselves is “Apsáalooke” and it means “children of the large-beaked birds.” So when I was a kid I thought of my ancestors as being these birds with huge beaks. I still kind of think about them that way (laughs).

They're trying to fly and reach towards the standard that's [been] set. It's symbolic of the blood quantum that's set by my tribe, but also all of the stereotypes and expectations that people put on Indigenous people: how you should look and the art you should make; everything, pretty much.

It’s talking about these standards that I set for myself and other people set for me and how it can feel like I'm always falling short of them.

And then this creature in the middle is a yellow mule. My [grandmother]’s last name was Dillon, but she was raised with her cousins, the Yellow Mules. In the Crow way, they're considered my grandparents also and they raised me as a grandchild. I wanted to think about putting a family symbol in there too as a kind of self-portrait.

Mules genetically can't have children because they're a mix of a horse and a donkey. I felt like I related to that a lot because if I were to have children with someone with a lower or equal blood quantum to me, then [the children] wouldn’t be considered Crow anymore. It’s a really strange position to be in. And it puts a lot of pressure on who I choose to date and all of these decisions that I wish I didn't have to put as much thought into.

I feel really proud of that piece because I think I was able to articulate a lot of things without having [very] complex symbolism.

Could I ask you about a more recent piece? It was a creature with a white space that contained a wooden spoon with salt and maybe a chicken and flowers.

This is one of the ones that fell somewhere between being a creature with little meaning and something with symbolism. I draw a lot of these weird in-betweens because sometimes it takes me a couple iterations to make the creature that I feel like actually expresses what I'm trying to say.

This was the first time I tried using digital illustration.

I got a used iPad on Facebook Marketplace and was trying to experiment with the process of drawing digitally. I was going through a breakup at the time and my ex-partner had given me this tiny porcelain chicken and I lost it a week before we broke up. And it felt kind of symbolic of our relationship to me (laughs).

I ended up making a couple of pieces that had this little chicken trying to symbolize, like, holding onto something that's not there anymore. I don't totally know what animal this is, but it was trying to be this blobby creature that isn't really that defined, because I was having a hard time articulating what my emotions were. I knew it was kind of a good time for a transition in my life, but at the same time it felt bad.

[The story is] the creature ate the chicken and then it felt bad for eating the chicken so it ate the flowers to cheer up the chicken and then it makes chicken noises so as to comfort it. And then with the fish, [the creature] had eaten it before but it didn't think to give the fish something to sustain it in its stomach. So the fish has died and it's crying and it has been catching the tears in the spoon. It ended up being this really incoherent whimsical story.

Sometimes when I draw these weird in-between things where maybe there's symbolism but it's not quite evolved to a place where it can be articulated through visual language. I'll write the story out in words and put it next to the painting so people can see that chicken is about heartbreak and that's why it's sad.

You mentioned that it sometimes takes a few tries to articulate an emotion. Do you sometimes find that you don’t know what you’re trying to articulate until you see it mirrored back?

I think it's kind of 50/50. Sometimes I'll not really know how to process emotions and I'll just draw a bunch of stuff and sometimes it will mirror back to me what I'm thinking and kind of give me a better way to understand what I'm feeling. And other times I'll have a particular idea or emotion that I want to convey through the art. And then I'll think about different symbols or expressions or ways that I can try to communicate that.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Well, that’s all for today, folks. Thanks for being here. We’ll see you next week!

In the meantime, you can always reach me via email, the comment section below, or on the Elon Machine, @SavageLevenson.